He has several of these pages with no text, just images. I look at travel times, I realize that it's 27 hours by car from Calcutta to Bombay, how much more by train (plane?) in 1953? He's moving fast, being dropped into these places, time for a quick gin and tonic (good for the malaria, apparently invented by the British East India company), a sit in a wicker chair, a deal. I don't know what he was doing in the bank at the time - when we were born he was an inspections officer, finding fraud and gathering evidence for prosecution. This seems far from that. The more I look at the pictures, the more they amaze me: yes, the contrasts (the adults clothed, shod (though ties and jackets are off) while the kids, having left their shoes, splash in the pool); the composition (second photo: that relaxed hand draped over wicker in the foreground while kids mess with a chair in the middle ground and others swim in the background); the narrative (third: the birds eating what's left of tea after the chairs have been abandoned and the pool is cleared). What's he thinking? Who does he have to talk to? What is he trying to live with when he says: "British overseas life is an existence at once free and regimented, held in the balance of good taste and violence, the latter most often carrying the day."

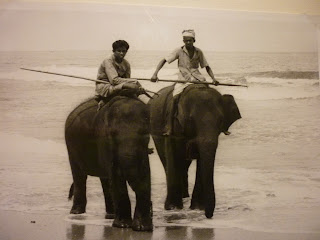

By the end of April he's in Ceylon (it will be called Sri Lanka as of 1972) on his way to Singapore. A single line of writing takes 20 minutes to realize: "After the heat of India, the itinerary leads to Singapore, with a first leg of the trip by Comet to Mount Lavinia." Did he fly on the first commercial jet liner, then? There's no declaration of wonder, no proclamation of firsts, but if he flew on a DeHavilland Comet, wow! (and whew!). Mount Lavinia turns out to be a suburb of Colombo, deeply steeped in the kind of colonial romance that rechristens a local dancer with the name of an epic heroine, names a city after her, and makes a hotel out of the governor's mansion in 1947, one that is still thriving (and makes post-colonialism look like a pipe-dream). If he stayed there in 1953, he left for walks on the beach pretty quickly - those are the only pictures: catamarans pulling up to excited children, long stretches of ocean (thoughts of 1937-1948 in the Navy? maybe not at all), and then, the photograph above. No words on this page, just them, stopping me absolutely in my first flipping of this album two years ago. By the time I rushed in and asked him about them he had little to say about anything, but his eyes were mischievous and he was smiling when he said "They were just as surprised to see me as I was to see them." I pressed for more (why on the beach? where to? what for? the sounds? the movement?) but he had nothing more to say. Closed his eyes, kept smiling. I pull back now and I think of him standing on the beach, the surf coming in pretty loudly, those chains clinking, the elephants' heavy steps leaving eddies in the sand. He pulls out his beloved Leica and there's some kind of communication, the young men drawing their long elephant goads up, looking at him, he at them. If I know my dad (and I knew so little even though I know a lot), he would have thanked them by raising his right hand in greeting and tilting his head down and to the side with that wonderful smile that said "there's more to be said here than we can say." The camera would have fallen back on his chest, the strap pulling its weight against his neck. He would have breathed deeply and closed his eyes and maybe now thought of everything up until now. And then he would have walked on.

Beautiful and evocative, Anne. Thank you.

ReplyDelete